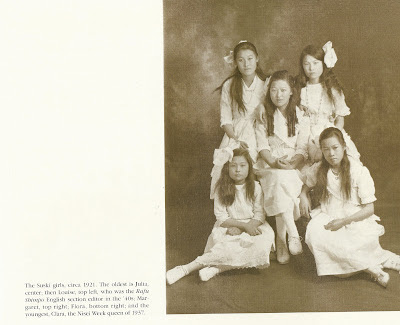

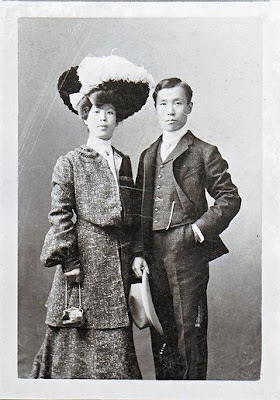

Albert Fairchild Saijo (1926-2011) was the author of numerous books and as equally skilled as a designer, woodworker, as he was a philosopher and poet. It appeared that life and its great, fathomless menagerie of art, language, and spirituality had always had its pull on him. His childhood was marked by the aspirations of his parents, and include a lovely pre-dawn vision of his mother scribbling poems and newspaper columns at her desk. He has also written about a copy of Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass, inscribed "Satoru Saijo November 1908, Chicago, Illinois in his strong hand with flourishes," a treasured momento from his father's early education in the US. At the turn of the century, Saijo's father worked as a domestic for the Albert Fairchild Holden family in Cleveland, who later sponsored him as a university student. In remembrance, Satoru's second-born son bears the family namesake: Albert Fairchild Saijo.

Editor Albert Saijo inspects a copy of Echoes, the Heart Mountain high school paper with co-editors Alice Tanouye and Hisako Takehara. Photographer: Hosokawa, Bill Heart Mountain, Wyoming. 6/43

At eighteen, Albert Saijo fought in Italy with the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, shortly after graduating from high school in Heart Mountain, Wyoming. In camp, a teenaged Saijo first learned of Rinzai monk Nyogen Senzaki, who held lectures and sittings in a barrack located in Block 2. Back in LA around 1950, Senzaki held zazen sessions twice a week in his tiny apartment on the 6th floor of the aging Miyako Hotel on the corner of E. 1st and San Pedro Street, which Saijo regularly attended and recalled, "Senzaki was seated in a Roman camp chair in front of the altar—before him was a folding card table & on it was the text of his lecture for that nite...his dentures creaked as he spoke." Although he was also in graduate school studying international politics at USC, Saijo dropped out, just as he began to suffocate from the city smog.

Allured by a blossoming literary renaissance, the young poet moved to San Francisco in the mid-fifties, where he found a job at the Chinatown YMCA. There, he met David Hunter, a pioneer in what later became known as the Human Potential Movement, which attracted others interested in alternative thinking. "When I first read about what his class was going to be in the office at the YMCA, it struck me that as very similar to things I had been active in LA. Mostly it was kind of zen-ish, it kind of appealed to me, and that’s why I went to the class and that’s where I met my initial friends mostly poets and writers and people in the arts and so forth. In the 50s, zen was just beginning to become an interesting subject. In fact, not many people had heard of zen." Also on the scene was a charismatic Englishman named Alan Watts, who taught Zen buddhism at the newly formed Academy of Asian Studies and had amassed a following through a regular program on KPFA, Berkeley's free radio station.

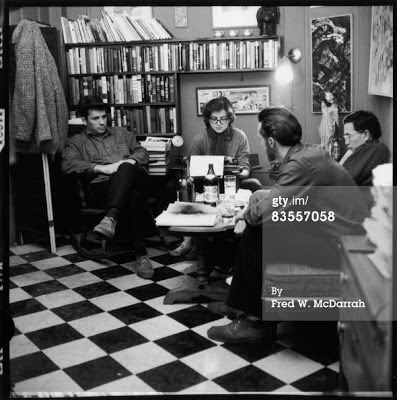

American writers Jack Kerouac (1922 - 1969) (left), Albert Saijo (right, with glasses), and Lew Welch (1926 - 1971) sit around a low table as they collaborate on a poem, which is typed by Gloria Schoffel in the apartment (304 W. 14th St.) of her and her soon-to-be husband, photographer McDarrah, New York, New York, December 10, 1959. The poem was entitled 'This is a Poem by Albert Saijo, Lew Welch, and Jack Kerouac' (later published as 'Trip Trap'), and was based on the trio's journey from San Francisco to New York in Welch's car. (Photo by Fred W. McDarrah/Getty Images)

Saijo soon bonded with Beat writers who were deeply influenced by East Asian art and poetry, sharing what he had learned from Nyogen Senzaki about zazen and his experiences in American concentration camps. The group of artists eventually formed the East-West House, where the residents expounded all hours on religion, philosophy, sex, and poetry. Saijo joined East-West House and later moved to a similar community home known as Hyphen House, located on the northwest corner of Post and Buchanan of San Francisco's Japantown, which was on the brink of a major city-led eradication in the name of "post-war redevelopment," forcing its JA residents to flee the neighborhood for the second time in a few decades.

"[Hyphen-House] was in a neighborhood half Black and half Japanese, with mostly Japanese shops and restaurants," Saijo wrote in a May 1973 recollection. "Then there was Jimbo's Bop City around the corner that opened after hours, and nearby Sullivan's Liquor Store that delivered both day and night...The area south of Post was being demolished. There were empty houses waiting with human detritus, eerie to explore. And there were cleared off lots already taken by lush grasses, and weeds like brome, dandelion, common mallow, and filaree and a few left-over stately trees, and drifts of trash...Hyphen-House was in a large wooden building painted battleship gray with a poolhall, shops, and restaurants at street level and five or six apartments in a row above. It had a second-story level overlooking Buchanan Street. We had the middle apartment. It was two storied with a commodious feel, especially downstairs where the ceiling was at least ten feet high."

In 1959, he took a remarkable cross-country trip to visit Allen Ginsberg at his apartment on the lower Eastside of New York with Lew Welch and Jack Kerouac, penning humorous haiku along the way that were later published in a volume titled Trip Trap: Haiku On The Road (simultaneously referring to Gary Snyder's book, Riprap and Kerouac's On the Road. ) Kerouac later memorialized their trip in his novel, Big Sur recasting Saijo as George Baso, "the little Japanese Zen master hepcat sitting crosslegged in the back of Dave's [Lew's] jeepster."

ALBERT

Lonely grain elevators

on Saturday

—Abandoned toys

By the time he had returned from the jeep trip, Saijo decided to abandon city life entirely, and set up residency in Marin County, with what he deemed "the Gary Snyder crowd." Snyder had a cabin in a part of Mill Valley known as Homestead Valley, and was neighbors with one of the original light show artists and sound engineer named Sandy Jacobs, who was married to Sumie Hasegawa, daughter of an influential Japanese painter, printmaker, and educator, Saburo Hasegawa. Although Saburo Hasegawa was a recent immigrant to the US, he was a serious practitioner of tea ceremony, calligraphy, and Zen buddhism. His arrival in San Francisco in the 50s was exquisitely timed with the growing movement of American buddhist studies, and he was quickly offered a position of lecturer at Alan Watt's Academy of Asian Studies, and then at the California College of Arts and Crafts.

Soon artists from San Francisco were trickling over the bridge into Marin, Bolinas, Inverness and Point Reyes Station, founding communes and farms. This also marked the beginning of Saijo's psychedelics period and experiments with peyote, mushrooms, and acid. By the "60s & 70s I WAS YOUR BASIC MARIN COUNTY HIPPIE STONER—LONG HAIR LOOSE CLOTHES FREE LIVING & ON THE FLOOR CUZ CHAIRS SEEMED A FORM OF REPRESSION...I CONSIDER MYSELF A CHILD OF THE 60S—IT WAS WHEN I BECAME A REBORN HUMAN."

When Snyder moved to Kyoto to study Zen, Saijo took over his humble cabin and also cooperated in the maintenance of a "floating zendo" for sitting meditation that Snyder and Whalen had established. He immersed himself in long hiking trips over the Inverness ridge and through the Sierra Nevada mountains and engaged in blissful fasts that lasted up to forty-five days.

By then, Albert's brother Gompers and his sister Hisayo had joined him in Mill Valley. The Saijo siblings were remarkably intertwined, with their lives overlapping and their homes often being exchanged with a certain ease; as one sibling would vacate, the next would move in. (According to Saijo's nephew Eric, Hisayo came up north, and hung around similar circles as Uncle Albert. In the 60s she even worked as Alan Watt's secretary on a houseboat.) He wrote and published The Backpacker, a straightforward guide to treading lightly and experiencing wilderness in 1972, with Gompers as illustrator.

After twenty years in Marin and a broken marriage, Saijo began the quest for a more solitary wilderness. With his new bride Laura, herself a musician and teacher, Saijo settled on California's Lost Coast, where the couple resided peacefully as homesteaders—clearing land, building a primitive shelter by hand, and gardening their own food for nearly twelve years. Albert and Laura moved to the Big Island in the 90s, claiming a small plot in a upland forest beneath Mt. Kilauea to build a second home of Saijo's own design. Six years later, his stream of conscious response to the world, Outspeaks, was published by Bamboo Ridge Press, unleashing Saijo's plaintive cry "UTOPIC MIND CAN'T EXIST IN CIVILIZATION BECAUSE UTOPIC MIND IS FREE OF THEORY & CIVILIZATION ISNOTHING ELSE—THE GOLDEN AGE CAN'T BE DESIGNED FROM OUTSIDE- IT MUST HAPPEN LIKE DAWN OR DARWIN'S FINCHES" or "I WANT TO RHAPSODIZE BUT I WOULD NOT BE PUT INTO ANY LITERARY CATEGORY I AM AN ANIMAL IN A CAGE & I AM BARKING TO BE LET OUT AS IT HAPPENS MY BARK IS RHAPSODIC"

Noone missed the unusual punctuation, or as long-time literary colleague Hisaye Yamamoto Desoto wrote, "At long last, Albert Fairchild Saijo has let loose his poems upon the world. Whether you read them in amazement, read them in an attitude of reverence, or read 'em and weep, they are not to ignore—the collection eschews the lower case entirely." Gary Snyder described it as "All caps and dashes, Albert Saijo's poem is a great life's strong song." In one particularly sensitive review, Juliana Spahr claims "Saijo writes a visual poetry of scribble and revelation in different colored inks. There is an interesting reproduction on the cover and there are tantalizing black and white glimpses of the visual poems throughout the book but the book itself presents word by word translations of these poems. Saijo, I want to argue, is a new Blake and his readers deserve an illustrated edition."

The poetic work (some may argue that they are rants) succinctly described Saijo's vision of human conflict and the environmental disasters we have brought to fore, and his role as an observer. The poetry also meanders on topics such as Saijo's constant battle to justify his use of resources, dependency on technology and the dreamstates he experiences in writing.

2 BOMBS

1

TERRORIST BOMB

HERE IS A BOMB— IT IS MADE OF WORDS— READ IT & IT GOES OFF IN YOUR HEAD & BLOWS YOU AWAY

2

BOOM

WOKE UP THIS MORNING TO FIND I HAD EXPLODED ALL OVER THE WORLD— I WAS BLOWN TO BITS— I WAS SCATTERED OVER THE WORLD IN SMALL PIECES— WHERE I USED TO BE WAS A BIG EMPTY HOLE THAT FAIRLY REEKED OF PEACE PAST UNDERSTANDING— I COULD NO LONGER SAY I EXISTED YET I WASNT EXACTLY DEAD— I HAD BECOME MYRIAD— EACH SMALL PIECE OF ME HAD REGENERATED INTO ANOTHER WHOLE ME & EACH WHOLE ME WAS STUCK TO SOME PART OF THE WORLD LIKE GUM OR SNOT — SO NOW WHEN THE WORLD WIGGLES EVERY LAST BIT OF ME WIGGLES IN UNISON

I count myself as one of the lucky few who were invited to spend a quiet afternoon in Albert and Laura's spare, warm home in Volcano, punctuated by her grand piano and the playful folk-style paintings by Gompers, to chew sandwiches and talk about a life of ecology framed through literature and language. Saijo died in the cottage he and his wife built together in the shadow of Kilauea, still an active volcano, on June 2, 2011. One bright spark in an indelible sea of ink.

"But you're out. You went away and you came back. Now as you head back to civilization, you have a wildness in your heart that wasn't there before. You know you're going outback again." —Albert Saijo, The Backpacker

NATUREMART

HOW VERY PRESUMPTUOUS OF US TO RESIGN UNILATERALLY FROM THE REST OF NATURE & MAKE EARTH SUN STARS ATMOSPHERE NEAR & DEEP SPACE INTO ONE BIG NATURAL RESOURCE CALLING FOR EARLY DEVELOPMENT IN HOMO SAPIENS' BEHALF SOLELY— HOW VERY PRESUMPTUOUS OF US WITH NO PARLEY TO TELL NATURE OK FROM NOW ON WE'RE TREATING YOU LIKE INSTAR HOROLOGII RATHER THAN INSTAR DIVINE ANIMALIS—KEPLER YOU BLEW IT— HOW VERY PRESUMPTUOUS OF US TO PLUNK OUR TRIP DOWN ON REST OF EARTH WITHOUT A NATUREWIDE REFERENDUM— BIBLE SEZ WE GOT DOMINION— BUDDHIST SAY LUCKY YOU BORN HUMAN & NOT A LESSER ANIMAL SO IT'S OK YOU TURN EARTH INTO INDUSTRIAL SITE & MORE ANGKOR WATS WHILE YOU'RE AT IT PLEASE— ANYWAY LIKE HUI NENG SEZ SINCE ALL IS VOID WHERE CAN THE DUST ALIGHT– EVEN THOREAU AT WALDEN WITH HIS I WANT TO MAKE THE EARTH SAY BEANS —RATHER THAN WHAT IT WAS SAYING BEFORE HENRY— WE LOOK AT PANORAMIC SCENERY & SAY IT LOOKS LIKE A PAINTING IN A GALLERY— WHATS OUR TRIP— CONTROL — DOMINATION— CAUGHT IN A TRULY MONSTROUS INSTANCE OF PATHETIC FALLACY— ANTHROPOMORPHIZE EARTH— TURN ALL OF NATURE INTO STOREBOUGHT— SCREW LOOSE IN BRAIN PAN MAKE EARTH LOOK LIKE GOODS ON STORE SHELF

### This article is the third in a series, briefly profiling the Saijo family. Albert was the only one I met in person, and I was blessed to befriend his nephew Eric, who subsequently shared his grandmother and father's stories.