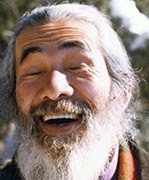

It is no great surprise that Eric Saijo's home is surrounded by a profusion of California native plants —ceanothus, manzanita, redbud—and the interior is richly punctuated with bronze bells and whimsical sculptures of turtles and owls. For years I've intended to find out more about Eric's father, Nisei artist Gompers Saijo, the eldest in an extraordinary family of artists and intellectuals who shared a profound reverence for the earth and were everything but conventional Americans. On the first day of April, the opportunity to do so appeared, and I stepped across the family's threshold.

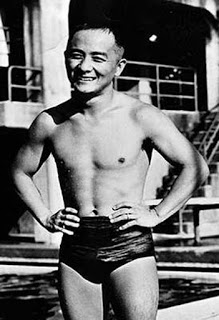

Gompers Saijo ((1922-2003)was given his unusual moniker by his Issei father, an immigrant who frequently went to the Port of Oakland to listen to Jack London and other longshoremen preaching the power of union organizing and labor rights on a soap box. Thus, he consciously named his first son after Samuel Gompers, the man who united the working class as the first and longest-serving president of the American Federation of Labor.

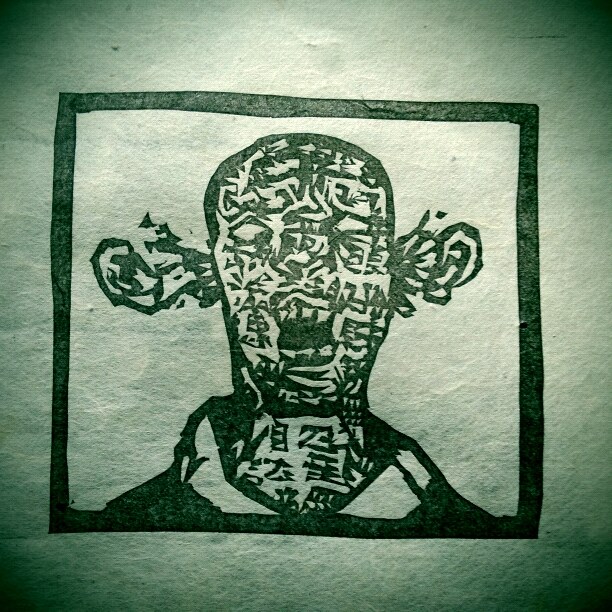

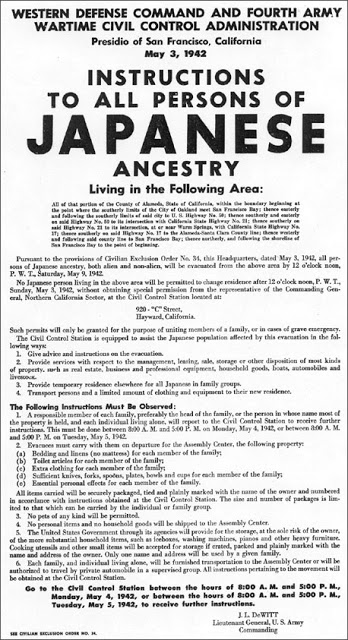

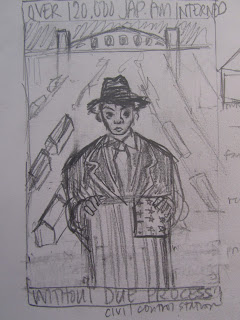

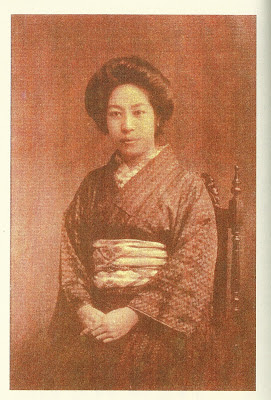

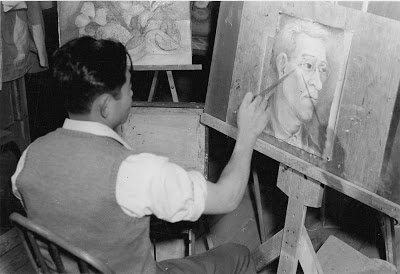

Gompers knew he was destined to be an artist. His mother, Asano Saijo, in addition to being a renowned haiku poet and Japanese language teacher, was a skilled practitioner of traditional Japanese brush painting and had instilled a unique sense of composition, space, and beauty in her children. While the children were raised humbly on a rural chicken farm in the San Gabriel Valley, there were always the sweet, dusty smells of meadows and creeks and the seasonal perfume of orange blossoms, interspersed by the drunken antics of annual kenjinkai picnics and the delights of Oshogatsu. Gompers was only twenty years old and in his second year of art studies at Pasadena City College when the U.S. entered into World War II. With the passage of E.O. 9066, the Saijo family was forced into the Pomona fairgrounds and in the summer of 1942, to Heart Mountain, Wyoming.

At the assembly center, Gompers encountered painter Benji Okubo (brother to Mine Okubo) who he described as "this guy who swaggers in with a sort of angry glare in his eyes…and is dressed like some buccaneer character off of a hollywood (sic) set…whoever, the initial image of benji (sic) has me totally blown away." Gompers also recalled meeting artist Hideo Date in the barracks, where he and Benji were working on an 8' x 20' painting to be used as a theatrical backdrop.

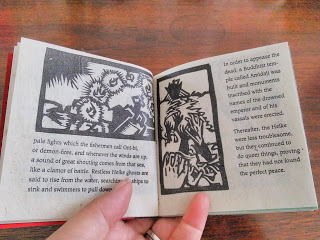

"The whole imagery was composed of flowing oriental lines and shapes painted in soft tonalities of mystically suggestive coloration. Never before or since have I seen the likes of this… " Okubo and Date, who were active with the Art Students League in Pasadena, founded by Morgan Rusel and S. Macdonald Wright, soon established the Art Students League Heart Mountain, a rigorous workshop where they expounded on spirituality, symbolism, and intellectualism through a myriad range of European, Mayan, Persian and Chinese arts and motifs that were carefully scrutinized and appreciated.

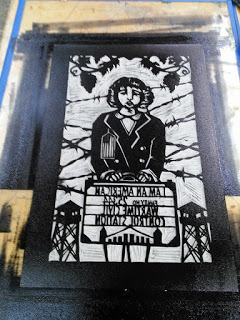

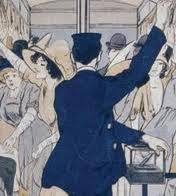

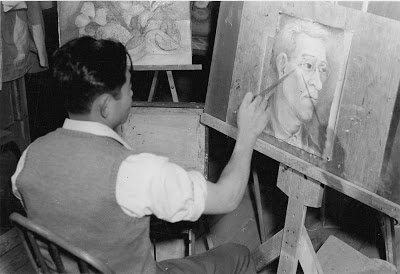

Okubo led his Issei and Nisei students through life drawing classes, utilizing a roll of tan-colored butcher paper, while lecturing on visual rhythmic patterns and abstract painting techniques using "prismatic colors almost out of the tube". The workshop completely engrossed Gompers, who even slept in the art studio at times. He also found work in the camp poster shop, silkscreening and mimeograph printing announcements for activities such as the haiku and shodo clubs that his mother finally had the leisure time to indulge in.

In 1943, when the "Statement of United States Citizen of Japanese Ancestry" form was distributed, Gomper's younger brother Albert joined the Army, but Gompers didn't. Confronted with the "loyalty questionnaire", Gompers refused to complete it, and considered himself a conscientious objector, claiming the right to refuse military service on the grounds of freedom of his beliefs. According to his son, Eric, his status as a resister was a point of distinction; he wanted his children to know that "that he never wanted to be a follower; that he was always looking for the unique path to take." After Albert left for basic training, Mother and Father Saijo and daughter Hisayo went to Cleveland, leaving Gompers alone at Heart Mountain. After witnessing the slumping, devastating effect that news of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima had on the camp's remaining residents, Gompers was ready to move on with his life. He moved briefly to Brooklyn, where he worked a string of odd jobs, including hand-painting chinaware.

Before long, the family reunited in Los Angeles, where Gomper began working as a sign painter and Albert attended classes at USC. When Albert joined a theatrical club known as Nisei Experimental Group, which included young writers such as Hiroshi Kashiwagi and Mary Oyama Wittmer (a passionate supporter, but not a member of the troupe), Gompers also got involved. As it turns out, he was also interested in NEG supporter Leonor De Queiroz, a young woman of half Japanese, half Mexican descent, who had always wistfully said she always wanted to marry an artist. She got her wish, and in 1951, Leonor and Gompers were married at the Los Angeles City Hall. Soon after, the couple spent a year in Mexico, hanging out with an avant-garde expatriate scene. Leonor had two aunts living in Mexico City who helped them find an apartment and make connections with both traditional and fine artists such as the Japanese Mexican muralist and landscape artist Luis Nishizawa.

In 1963, Gompers, Leonor, and their two children, Rani and Eric, moved from Los Angeles to San Francisco. Albert had moved up first, and in the late 50s, he bought a house in Mill Valley tucked into a dense forest of bay laurels, oaks, and redwoods at the foot of Mt. Tamalpais. However, while he was in the Army, he had contracted tuberculosis, so Albert was sent away to recover from a new bout. On his invitation, Gompers and family moved into Albert's house and never moved out. After Albert was released, he managed to buy the house right next door, so the two brothers lived side-by-side on a narrow, windy road for the next fourteen years. Eric recalls,"We could walk out of the house and at the end of the road just start out on trails into the woods. I remember going on numerous hikes with Dad, Uncle Albert or just us kids. Starting from kindergarten, we walked to school down a canyon with a creek running through it. "

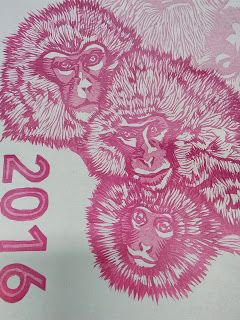

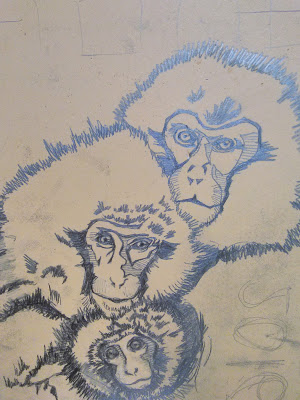

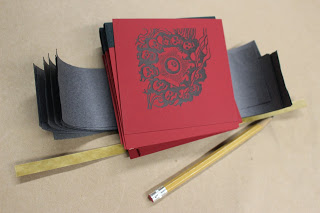

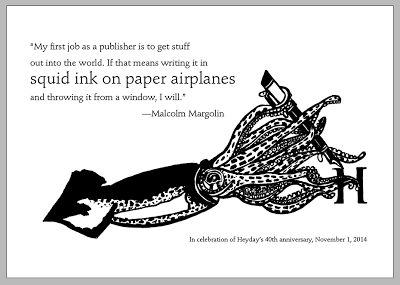

To support his family, Gompers adapted by becoming a jack of all trades. "He had a basement workshop where he made paper-mache sculptures or wood sculptures, " says Eric, "and spent a phenomenal amount of time on each piece." This menagerie, inspired by folk art and patterns, were sold through Gump's San Francisco. Additionally, he did freelance work for Now Designs kitchen products, remodeled homes and decks, and did spot illustration on contract. In the 60s and early 70s, Gomper's illustrative acumen hit its stride, and he began utilizing his bold sense of line to print highly coveted, psychedelic posters for the Haight Ashbury scene, which led to an unexpected partnership with one independent publisher.

Zen Benefit Poster for the Zen Mountain Center, featuring Gary Snyder: Poetry with Mahalilia Mandalagraphy at the Fillmore Theater, by Gompers Saijo, circa1960.

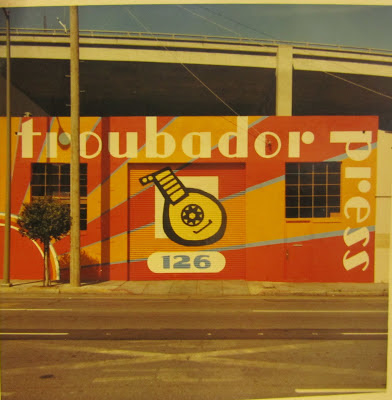

"Gompers had this low slow voice; he always wore a kerchief wrapped around his forehead. He had this lovely color and dark hair- most people probably assumed he was Indian, " reminisced Malcolm Whyte, publisher of Troubador Press.

When Troubador moved into a space at 126 Folsom Street, Whyte hired Gompers to design and paint the press' lute logo in a supergraphics style popular in the 70s on the building's rollup door, and remembers watching Gompers using a chalked snapline to mark out the sunburst design with absolute precision.

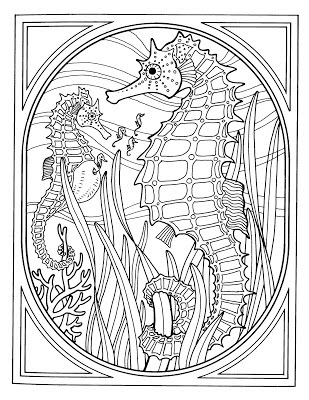

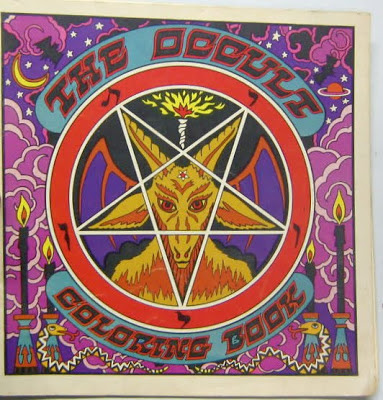

"Gompers' first book with us was a big, oversized 12" x 12" occult coloring book that came out in 1971, marketed for the emerging hippie audience, people into astrology and all that stuff". "Noone would let you publish that with that name these days, but we sold 12-13,000 copies".

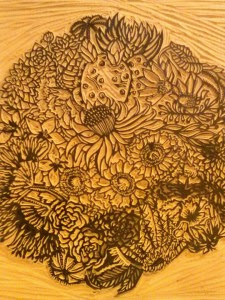

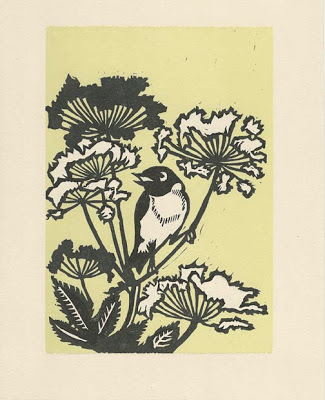

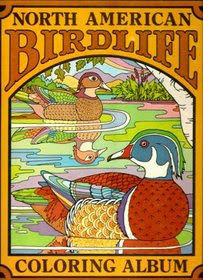

Over the next few years, Gompers produced six coloring books with Troubador on birds, wildflowers, wildlife and jungles with great success; the sealife coloring book alone sold 190,000 copies.

North American Birdlife Coloring Book by Gompers Saijo, Troubador Press, 1972.

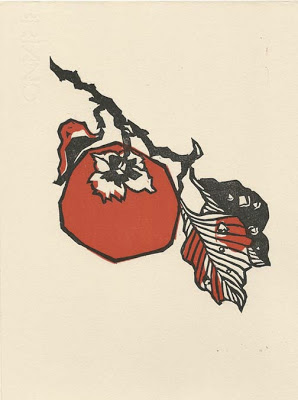

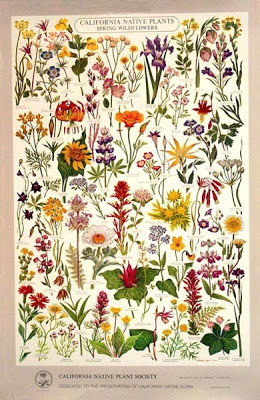

The coloring books demonstrated his gradual shift of interests into nature. In 1972, Albert published

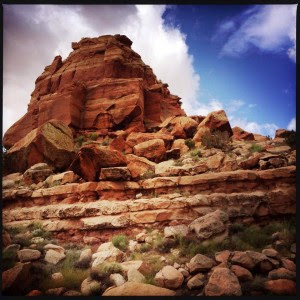

The Backpacker , a semi-spiritual how-to guide on traversing lightly while hiking in nature, with black and white illustrations by Gompers. As his connection to the flora and fauna of California deepened, Gompers began a series of spring and desert wildflowers, which were first published as posters by the California Native Plant Society in 1979 and 1981, selling more than 120,000 posters. An early member of the

Marin Chapter of CNPS,

Gompers also designed their logo featuring the Tiburon Mariposa Lily, and created the poster for the chapter’s first plant sale.

Both brothers moved to the remote fogbelt of California's Northern Lost Coast in the 70s, where Gompers rented a cabin to work on a series of landscapes in oils and pastels. There, he produced astoundingly beautiful drawings that reached for that essence of wild and open abandonment of the region's grass prairies and staggering cliffs. After a decade, Albert left California to move to Volcano, Hawai'i, and eventually Gompers also returned to the Bay Area, where his final works of art had a clear Asian influence. He died in Point Reyes Station in 2003.

He didn't keep a diary, but what remains are nearly a thousand sketchbooks, most of which are in Eric's basement in Oakland. These sketchbooks show a total love and desire to understand the western landscape, and what is equally amazing is the determination with which he approached the same scenes again and again with his pencil or pastels. Gompers didn't exhibit much at all, so the memories of this remarkable Nisei's contributions on earth are as ephemeral as the bloom of an indigenous shooting star. He once said, “To love flowers is to make some deep connections between the animal and plant kingdoms, the knowledge of complete inter-dependence, a symbiosis of all earthly manifestations that can only be sustained by love.”

My sincere and humble thanks to Eric Saijo for his patience and allowing me access to family archives and interviews.