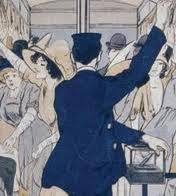

"Inside the air was a pestilence; it was heavy with disease and the emanations from many bodies. Anyone leaving this working mass, anyone coming into it...forced the people into still closer, still more indecent, still more immoral contact. A bishop embraced a stout grandmother, a tender girl touched limbs with a city sport, refined women's faces burned with shame and indignation—but there was no relief. Was all this an oriental prison? Was it in some hall devoted to the pleasures of the habitues of vice? Was it a place of punishment for the wicked? No gentle reader, it was only the result of public stupidity and apathy. It was in a Los Angeles streetcar on the 9th day of December, in the year of grace 1912.

— "A Section of Hades in Los Angeles," Los Angeles Record, December 11, 1912.

Los Angeles' general public has always been one of tremendous ethnic diversity, a resilient mixture of Mexicans, Chinese, Japanese, Native Americans, African Americans, Midwesterners, Jews, Germans, Scots, Greeks, Italians, and "Okies." The beach was a natural recreational escape for Los Angeles' expanding immigrant class, and once the Santa Monica Air-Pacific Electric streetcar line went from downtown to the beach, it provided accessibility to pleasure seekers of myriad ethnicities, so long as they could afford the train fare. Early in the century, numerous amusement parks including Venice Pier, Ocean Park Pier and the Long Beach Pike rimmed the Pacific Ocean and were even connected to each other by train. With their carnival atmosphere and rowdy good humor, these parks allowed Angelenos and tourists to immerse themselves into mainstream modern American culture. by abandoning oneself to mixing with an anonymous crowd.

Historian Eric Avila argues that the disappearance of streetcars, which began in the 30s and continued well into the 50s, severely undermined the popularity of the amusement park, the urban ballpark, and other public cultural institutions whose inner-city location gradually lost favor. A new generation of more affluent motorists were more likely to engage in activities that were increasingly dictated by the availability of parking space.

But by the end of World War II, more and more of Los Angeles was dedicated to privatizing exclusive space away from the larger social identity of the city. Compared to the unruly crowds and the threat of an unhygienic beach, swimming pools presented a regimented, controlled landscape that orchestrated the movement and interactions of swimmers. Eventually, those who could afford to built private pools in their suburban backyards, further distancing themselves from the larger social and sexual identities of the city.