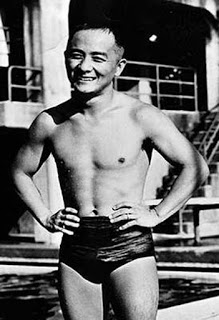

Sammy Lee, first Asian American gold medalist.

As a twelve-year-old Angeleno in 1932, Korean American athlete "Sammy" Lee dreamed of becoming a world-class competitive diver, but at the time, Latinos, Asians and African-Americans were only allowed to use the Brookside Park Plunge (Pasadena's public pool), on Wednesdays, on what was called “international day”: the day before the pool was scheduled to be drained and refilled with clean water. Because Lee needed a place to practice and could not regularly use the public pool, his diving coach dug a pit in his backyard and filled it with sand, which Lee used to practiced his dives in, despite bone-jarring impacts upon landing. In spite of the bigotry, in the summer of 1948, "Sammy" Lee became the first Asian American to win a gold medal in the Olympic Games held in London, and the first man to win back-to-back gold medals in Olympic platform diving.

Early city parks and playground ordinance in the early 20th century made no reference to race, but by the 1920s, everything had changed and rules proclaiming pools "For Whites Only" barred low-income, people of color from access. With few exceptions, Southern California’s public beaches were off limits. In those days, people of color had two choices: a 200 foot roped-off stretch of the Santa Monica beach designated "For Negros only" known as the "Inkwell", and Bruce's Beach in nearby Manhattan Beach. When Manhattan Beach was incorporated in 1912, a two block stretch was designated as an all-African American resort, owned and operated by Charles and Willa Bruce. Both of these segregated beaches provided refuge and relief for minorities who wanted visit the ocean and enjoy the good life promised in Southern California without harassment. But by 1920, even Bruce's Beach was also proclaimed off limits, marked with "No Trespassing: signs although it was city owned.

"Hayride at Bruce's Beach, c. 1920s" When Manhattan Beach (in Los Angeles) was incorporated in 1912, a two-block area on the ocean was set aside for African-Americans.

An end to racial segregation in municipal swimming pools was ordered in summer 1931 by Superior Court Judge Walter S. Gates after Ethel Prioleau, an African American widow of an Army major, sued the city, complaining that she was not allowed to use the swimming pool in nearby Exposition Park but had to travel 3.6 miles to the "negro swimming pool" at 1357 East 22nd street. Other city pools were opened to Negroes but closed to whites one day a week, although in most of South Central and East LA suffered from a complete lack of parks and pools. As the city grew, and as racial housing restrictions were finally overturned by the Supreme Court in the late 1940s and early 1950s, the racial and ethnic geography of Los Angeles changed, but so did the growing preference of privatized, and predictable recreation which required entrance fees. Changes in technology and the growth of white suburban neighborhoods brought an unprecedented boom of private swimming pools in the mid-1950s, which only further widened the race and class divisions in LA.

After the Los Angeles Playground Commission initiated a policy of discriminating against people of color in 1925, the local chapter of the NAACP went into action. The name of the case was "George Cushnie v. City of Los Angeles" but locally it was known as "The Bath House Battle." Although the original case determined that the city had provided facilities "separate but equal" enough to comply with the 14th amendment. That wasn't enough for civil rights activist Betty Hill, who was determined to win through persistence. She went to court 25 times over a period of several years and lobbied each city councilperson individually until 1931 when Judge Walter S. Gates decided that the Playground Commission could not continue its policy of discrimination. This became known as the infamous “swimming pool case.”

In addition to the history of swimming pools and racial covenants, I'm exploring other aspects of swimming pool culture as it emerged in the city. While Los Angeles isn't the birthplace of the swimming suit, Hollywood in particular has singlehandedly developed the lasting, popular vision of swimming attire and the lifestyle it lends- cosmopolitan, sexy, and relaxed- since only the most successful could lead a life of lassitude spent by the pool, working on one's tan. Suntans and sunbathing is another bizarre ritual (particularly to people of color) that might be examined, especially when reviewed with today's UV ray and the particular elements of Los Angeles' air.

The environmental impact of swimming pools is also of great interest. In 2004, the LA Times reported that 19,659 gallons of water evaporate from a typical uncovered pool each year, according to estimates from the Metropolitan Water District. I'd be curious to further research the average annual water used to fill LA's swimming pools, the gallons of chemicals used, and perhaps interview one pool service company on a daily routine as they go from home to home (or neighborhood pool to neighborhood pool) to clean, chlorinate, and care for the city's pools.

Finally, there are the stories connected to abandoned pools. With the recent foreclosure of homes on the rise, festering swimming pools, fetid and green, that harbor mosquitos and other pests has given rise to concerns about West Nile virus and other transmittable diseases, which I understand has led to helicopter surveillance of murky swimming pools. In suburban Los Angeles, dry pools are the playgrounds of skateboarders, another major culture that emerged out of Southern California, who use the concrete bowls to perfect their acrobatic vertical aerials. Sharing maps of abandoned pools to drain and skate in have been part of the secret lives of skaters for decades.